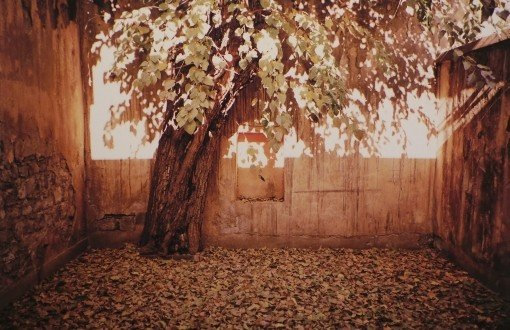

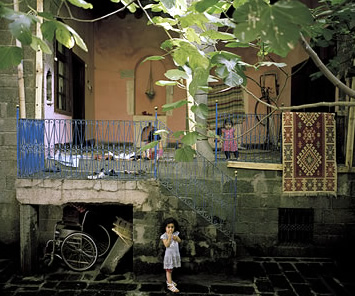

In one of the most impressive photographs of the Helen Sheehan exhibition at Depo, a Kurdish boy sits on a turquoise wall in the former Armenian quarter in Diyarbakır, looking away dreamily. At the entrance of the adjoining house stands a young woman, looking at the camera with a rather harsh expression on her face. It is as if they belong to different worlds despite their proximity. Another picture shows a mulberry tree at the garden of the St. Giragos church in Diyarbakır. A fountain at the entrance to Zeytun (now renamed Süleymanlı) in the Ciclia region bears witness to a century where societal violence has been the rule rather than the exception. In a fourth photograph we are presented with an abandoned Armenian house, also in Diyarbakır. It has many doors and windows inside but sadly, no one seems to live there anymore.

These are some of the lost landscapes in Helen Sheehan's "Armenian Family Stories and Lost Landscapes" exhibition at Depo, located in a former tobacco warehouse ("Tütün Deposu") in Istanbul's Tophane district. In May 2014, Sheehan had exhibited her photographic sound pieces inside the restored Armenian church of St. Giragos in Diyarbakır. Her interest in Armenia and its diaspora was triggered while working as a teacher in Venice. Sheehan started working on a Ph.D. titled "Contemporary Armenian Exiles, objects narratives, histories" at the London College of Communication in 2009 but could get no funding to continue her studies.

"The Armenian families that I worked with in diaspora in Paris and London, all had these extraordinary links to Diyarbakır in their family histories and this led me to that city and the old Armenian quarter," Sheehan told me.

"I met Seta Tahan Bilezikian who is in her 80s now in Paris and she opened up her family archive about her grandfather Boghos Sarrafian who was one of the famous photographers. What is extraordinary is that in Diyarbakır itself, there is no trace of their existence in that city and yet they had set up the first photographic studio there."

As she explored the traces of the Sarrafian family, Sheehan discovered how Abraham, Boghos and Samuel Sarrafian traveled and recorded pictures of Beirut, Diyarbakır, Gaziantep and Mardin and used them in postcards that proved very popular at the time. "It was extraordinary really because here were these brothers who had taken some of the most beautiful and iconic photographs of the Middle East, were fluent in Arabic, French, Armenian and Turkish and yet their existence was not even registered in the town of their birth."

Sheehan, who has contributed to the BBC World Service, The Independent , AI C2 magazine and Elle Sweden has photographed the destruction of Sarajevo, Mostar and Vukovar in the 1990s. Her photographs were exhibited with Amnesty International in different European cities. But it was the lost landscapes project that had the most lasting impact in her career. She is a recipient of a funding award for this exhibition from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and Culture Ireland.

"Seta who retains the family memory spoke with great pride not just about their photographic achievements but also about their work with helping victims of 1915 who came to the Lebanon in desperation or ended up there after the deportations," she said.

"The Sarrafians themselves fled during the pogroms of the Abdülhamid II period in the 1890s. I found the intimacy of their family album as a testament to a disappeared existence which is the case with so many Armenian families. Seta also presented me with a beautiful scarf which is made of silver and gauze net material that her grandmother Anne Tufenkian Sarrafian wore in Diyarbakır. I find these objects very touching and part of the missing social history of the region."

For Sheehan the project also had a personal aspect. As an Irish artist she is painfully aware of the oppression of people and their language by others. "In Ireland we live on the edge of Europe and in our past spoke a different language which is now very much a marginal language in our own country, Irish," she said. "I speak better French and Italian. It is also about not having had a voice as a people in our history, about colonialism and its destruction and consequences. However the resurfacing of memory can also be healing as although we cannot bring back the past, we can look at it through the family archive. In Ireland we now work together peacefully recognizing differences."

"In searching for the Armenian past I am also confronting my own family history as it too resurfaces through the family albums of my cousins and family who live on either side of the border in Ireland," she added.

Kaya Genç :

Daily Sabah, January 24. 2015